Outsmarting Pancreatic Cancer

BU researchers are developing an antibody drug they hope will help halt the rapid spread of pancreatic cancer.

Anyone who’s watched a loved one die of pancreatic cancer knows that it’s a fast-moving and cruel disease. By the time symptoms appear, it has often spread to other organs. Prognoses are grim—rarely more than a few years, sometimes less than a month.

One contributing factor to the low survival rate may be the disease’s resistance to drugs called checkpoint inhibitors that have been effective in more than a dozen different cancers. These drugs block proteins that cancer cells use to hide from the immune system, but not in pancreatic cancer.

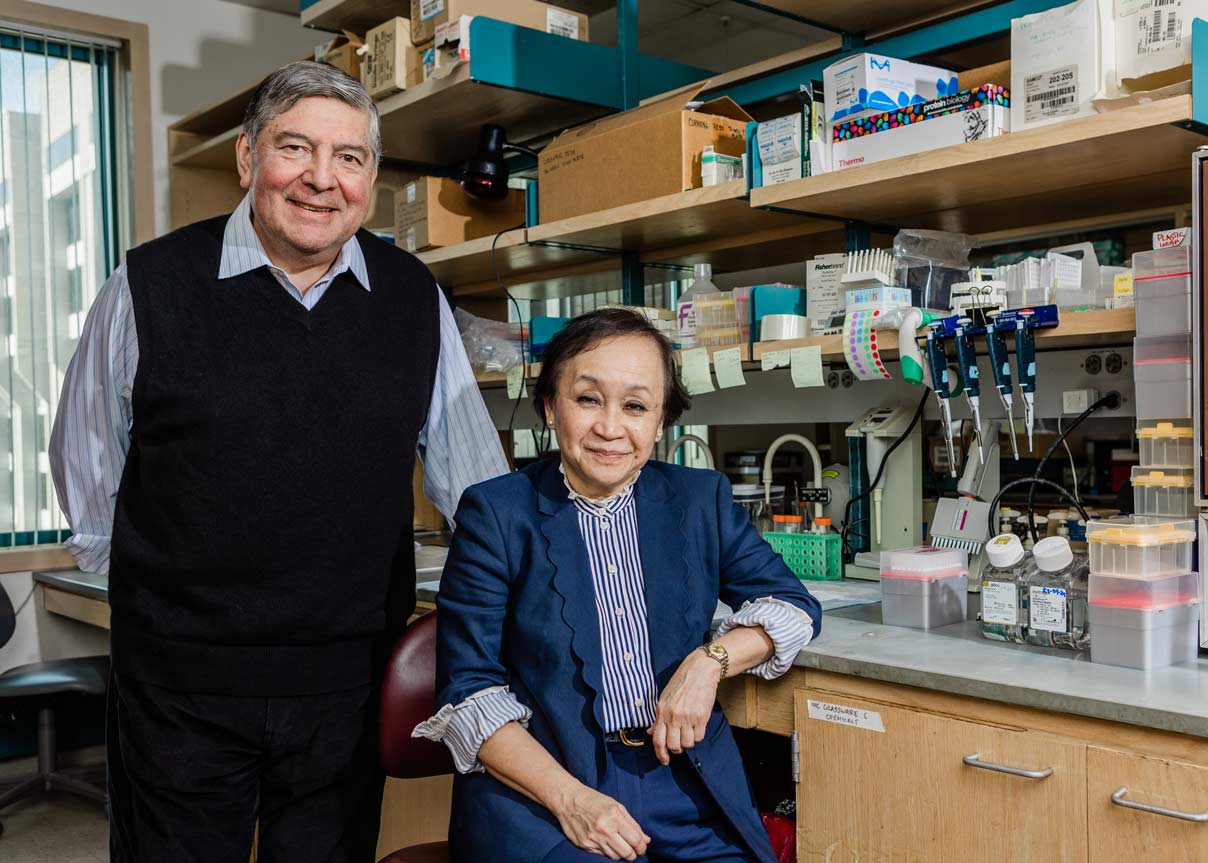

The disease’s evasive maneuvering may be coming to an end, however, if BU medical researchers Victoria Herrera and Nelson Ruiz-Opazo have their way. They hope their drug will work in concert with immune checkpoint inhibitors to keep cancer cells from escaping the immune system and, in turn, halt the spread of microtumors already on the move by the time a patient is diagnosed.

In consultation with Matthew Kulke, BU’s Zoltan Kohn Professor of Medicine and chief of hematology and oncology at Boston Medical Center, the University’s primary teaching hospital, their research was one of six projects supported by a 2024 BU Ignition Award, designed to accelerate the advancement of promising new science and technology and ultimately identify a viable pathway to bring a new product to market. Herrera and Ruiz-Opazo will work with Kulke to test the antibody drug.

Professors of medicine at BU’s Whitaker Cardiovascular Institute, Herrera and Ruiz-Opazo are targeting a gene called DEspR, which is not present on normal adult pancreatic cells but is seen on tumor cells and at elevated levels on cancer stem cells. The gene is also expressed on certain immune cells that, paradoxically, help cancer evade the immune system.

By simultaneously shutting off these “culprit” cells that express DEspR, while leaving normal cells with no DEspR intact, their goal is to inhibit DEspR’s collaborative roles in metastasis and immune evasion. If successful, this dual action outsmarts pancreatic cancer and could mean reducing or eliminating the use of chemotherapy, with its debilitating side effects.

“We scientifically project, and genuinely hope,” Herrera says, “that anti-DEspR will prolong life and reduce the hardship of pancreatic cancer as a disease.”