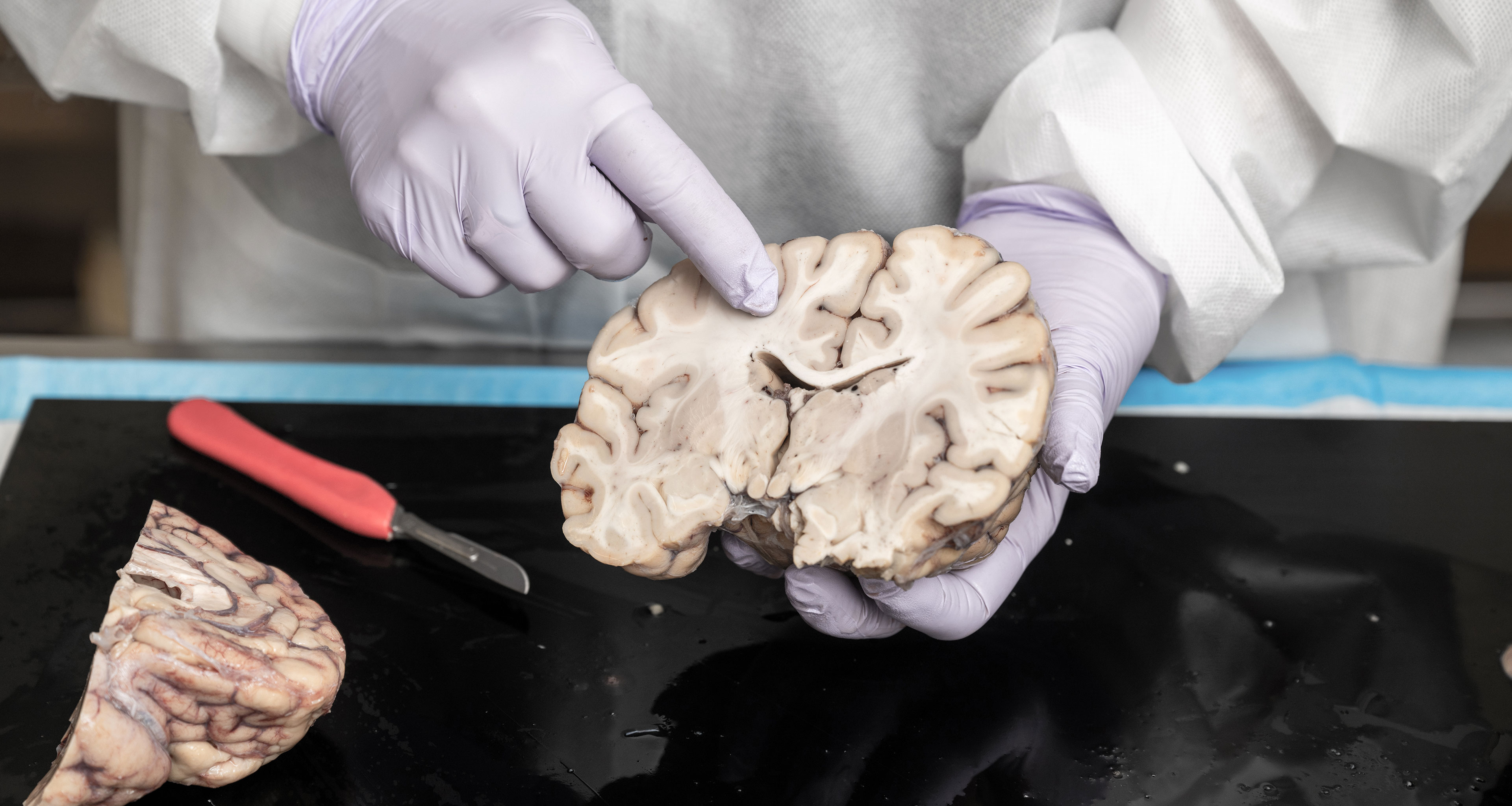

Above: A new project at BU’s CTE Center looks for biological markers that indicate brain disease resulting from head trauma.

$15M NIH grant bolsters University efforts to diagnose a brain disease afflicting athletes and veterans

One tragic aspect of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, the neurodegenerative disease linked to repeated head trauma, is that diagnosis always comes too late—after death.

A new study led by Boston University’s CTE Center aims to change that.

Funded by the National Institutes of Health, the DIAGNOSE CTE Research Project–II will explore whether bloodwork and advanced brain imaging can identify biological markers of CTE. A diagnosis in living patients would open the door to potential treatments and offer hope to devastated families. The project builds on BU’s first DIAGNOSE CTE study, launched in 2015, which helped define the disease’s symptoms, including memory loss, difficulty solving problems, aggression, and poor impulse control.

CTE is a risk for those who played contact sports like football and hockey as well as for those who served in the military. BU neurologist Jesse Mez recently conducted the largest study of male hockey players’ brains, finding that the odds of developing CTE increased by 34% for each year of play. The results were published in December 2024 in JAMA Network Open.

Increase in chance for male hockey players to develop CTE, with each successive season

BU will form a research consortium led by Michael Alosco, associate professor of neurology, and Robert Stern, professor of neurology, neurosurgery, and anatomy and neurobiology, along with experts from other institutions. The study will enroll 350 people—including 225 former college and pro football players—for neurological exams, scans, and blood tests. Among them is former NFL quarterback Matt Hasselbeck. “I’m choosing to volunteer for DIAGNOSE CTE II to honor my teammates, especially those who blocked for me and took hits to the head so that I didn’t have to.”